|

|

|

Home | Pregnancy Timeline | News Alerts |News Archive July 7, 2014

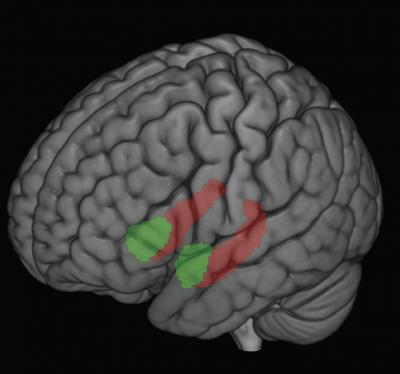

Different forms of early life stress, such as child maltreatment or poverty,

impacted the size of two important brain regions: the hippocampus

(shown in red) and amygdala (shown in green), according to new

University of Wisconsin–Madison research.

Children who experienced such stress had small amygdalae and hippocampai,

which was related to behavioral problems in these same individuals.

Image: courtesy of Jamie Hanson and Seth Pollak |

|

|

|

|

|

Child life stress can leave lasting impact on brain

For children, stress can go a long way. A little bit provides a platform for learning, adapting and coping. But a lot of chronic, stress like poverty, neglect and physical abuse is toxic and can have lasting negative impacts.

A team of University of Wisconsin-Madison researchers recently showed these kinds of stressors, experienced in early life, might be changing the parts of developing children's brains responsible for learning, memory and the processing of stress and emotion. These changes may be tied to negative impacts on behavior, health, employment and even the choice of romantic partners later in life.

The study, published in the journal Biological Psychiatry, could be important for public policy leaders, economists and epidemiologists, among others, says study lead author and recent UW Ph.D. graduate Jamie Hanson.

"We haven't really understood why things that happen when you're 2, 3, 4 years old stay with you and have a lasting impact," says Seth Pollak, co-leader of the study and UW-Madison professor of psychology.

Early life stress has been tied before to depression, anxiety, heart disease, cancer, and a lack of educational and employment success, says Pollak, who is also director of the UW Waisman Center's Child Emotion Research Laboratory.

"Given how costly these early stressful experiences are for society … unless we understand what part of the brain is affected, we won't be able to tailor a response," he adds.

For the study, the team recruited 128 children around age 12 who had experienced either physical abuse, neglect early in life or came from low socioeconomic status households.

Through extensive interviews with the children and their caregivers, researchers documented behavioral problems and the cumulative life stress. Then took images of the children's brains, focusing on the hippocampus and amygdala, (both involved in emotion and stress processing). These images were compared to similar aged children from middle-class households who had not been maltreated or experienced similar stresses. Although the hippocampus and amygdala are very small (the word amygdala is Greek for almond), their measurements found that children who experienced any of the three types of early life stress had smaller amygdalas than children who had not.

Children from low socioeconomic status households and children who had been physically abused had smaller hippocampus volumes, as did children with behavioral problems and increasingly cumulative life stresses.

Why early life stress may lead to smaller brain structures is unknown, says Hanson, now a postdoctoral researcher at Duke University's Laboratory for NeuroGenetics, but a smaller hippocampus is a demonstrated risk factor for negative outcomes. The amygdala is much less understood and future work will focus on the significance of these volume changes.

"For me, it's an important reminder that as a society we need to attend to the types of experiences children are having," Pollak says. "We are shaping the people these individuals will become."

But the findings are just markers for neurobiological change; a display of the robustness of the human brain, the flexibility of human biology. They aren't a crystal ball to be used to see the future, say Hanson and Pollak.

Abstract

Background

Early life stress (ELS) can compromise development, with higher amounts of adversity linked to behavior problems. To understand this linkage, a growing body of research has examined two brain regions involved with socio-emotional functioning- the amygdala and hippocampus. Yet empirical studies have reported increases, decreases, and also no differences within human and non-human animal samples exposed to different forms of ELS. Divergence in findings may stem from methodological factors and/or non-linear effects of ELS.

Methods

We completed rigorous hand-tracing of the amygdala and hippocampus in three samples of children who suffered different forms of ELS (i.e., physical abuse, early neglect, or low SES). In addition, interview-based measures of cumulative life stress were also collected with children and their parents or guardians. These same measures were also collected in a fourth sample of comparison children who had not suffered any of these forms of ELS.

Results

Smaller amygdala volumes were found for children exposed to these different forms of ELS. Smaller hippocampal volumes were also noted for children who suffered physical abuse or from low SES-households. Smaller amygdala and hippocampal volumes were also associated with greater cumulative stress exposure and also behavior problems. Hippocampal volumes partially mediated the relationship between ELS and greater behavior problems.

Conclusions

This study suggests ELS may shape the development of brain areas involved with emotion processing and regulation in similar ways. Differences in the amygdala and hippocampus may be a shared diathesis for later negative outcomes related to ELS.

Return to top of page |