|

|

Developmental Biology - Brain Memory Enhancement

Weak Current Can Retrieve Lost Memories

A small electrical zap to the brain could help you retrieve a forgotten memory...

A study by UCLA psychologists provides strong evidence that a specific region of the brain plays a critical role in memory recall. The research, published in the Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, for the first time shows how using an electrical current to stimulate this region, the left rostrolateral prefrontal cortex (RLPFC), improves people's ability to retrieve memories.

"We found dramatically improved memory performance when we increased the excitability of this region," explains Jesse Rissman, a UCLA assistant professor of psychology, psychiatry and biobehavioral sciences, and the study's senior author.

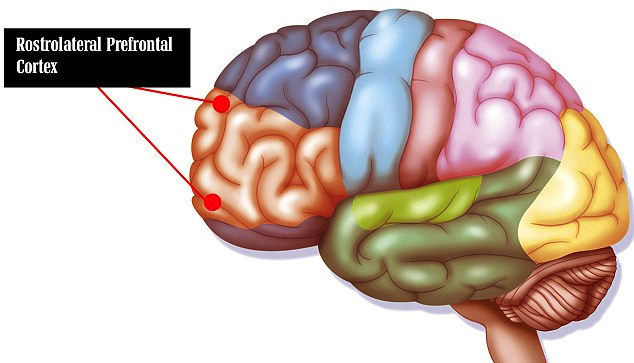

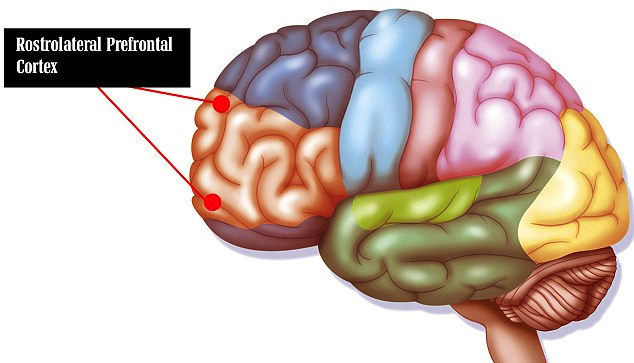

The left rostrolateral prefrontal cortex is important for high-level thought, including monitoring and integrating information processed in other areas of the brain. This area is located behind the left side of the forehead, between eyebrow and hairline.

"We think this brain area is particularly important in accessing knowledge formed in the past and making decisions based upon it," said Rissman, a member of the UCLA Brain Research Institute.

The psychologists conducted experiments with three groups of people whose average age was 20. Each group contained 13 women and 11 men. Participants were shown a series of 80 words on a computer screen. With each new word, participants were instructed to imagine themselves or another person interacting with the word — to help "self" or "other" also appeared on the screen. For example — the combination of "gold" and "other" might prompt them to imagine a friend with a gold necklace.

The following day, participants returned to the laboratory for three tests — (1) one of memory, (2) of reasoning ability and (3) visual perception. Each participant wore a device sending a weak electrical current through an electrode on the scalp to decrease or increase the excitability of neurons in the left rostrolateral prefrontal cortex. According to Rissman, increasing nerve excitability makes neurons more likely to fire and enhance connections.

The technique, called transcranial direct current stimulation, or tDCS, gives most people a warm, mild tingling sensation for the first few minutes, said study lead author, Andrew Westphal, now a postdoctoral scholar in neurology at University of California San Francisco.

For the first half of the hour-long study, all participants received "sham" stimulation — meaning the device was turned on just briefly, to give the sensation that something was happening — and then turned off with no electrical stimulation applied. This allowed researchers to establish a baseline for each participant under normal conditions. For the next 30 minutes, one group received electrical current that increased neuronal excitability, a second group received current suppressing neuronal activity, and the third group received only sham stimulation. Researchers then analyzed each group to find which had the best recall of the words seen the previous day.

The scientists noted there were no differences among the three groups during the first half of the study — when no brain stimulation was actually used — so any differences in the second half of the experiment could now be attributed to brain stimulation, Westphal added.

Memory scores for the group whose neurons received excitatory stimulation during the second half of the study were 15.4 percentage points higher than their scores when they received the sham stimulation.

Scores for those who received fake stimulation during both sessions increased by only 2.6 percentage points from the first to the second session — a statistically insignificant change likely due to increased familiarity with the task. Scores for the group whose neural activity was temporarily suppressed increased by just five percentage points, which the authors believe was not statistically significant as well.

"Our previous neuroimaging studies showed the left rostrolateral prefrontal cortex is highly engaged during memory retrieval. The fact that people do better on this memory task when we excite the region with electrical stimulation provides causal evidence that the RLPFC contributes to the act of memory retrieval. We didn't expect the application of weak electrical brain stimulation would magically make memories perfect, but the fact that performance increased as much as it did is surprising and is an encouraging sign that this method could potentially be used to boost people's memories."

Jesse Rissman PhD, Associate Professor, Departments of Psychology and Psychiatry & Biobehavioral Sciences, University of California Los Angeles.

For the final task focusing on perception, subjects were asked to select which of four words has the most straight lines in its printed form. Among the words "symbol," "museum," "painter" and "energy," only the word "museum" has the most straight lines. Researchers found no significant differences among the three groups — which Rissman said was expected. "We expected to find improvement in memory, and we did," Rissman said. "We also predicted the reasoning task might improve with the increased excitability, and it did not. We didn't think this brain region would be important for the perception task."

Why do people forget names and other words? Sometimes it's because they don't pay attention when they first hear or see the word, so no memory is even formed. In those cases, electrical stimulation would not help. But in cases where a memory does form but is difficult to retrieve, stimulation could help access that memory.

"Stimulation is helping people to access memories that they might otherwise have reported as forgotten."

Andrew J. Westphal, MSAA, PhD, University of California, Berkeley, Space Sciences Laboratory.

Although tDCS devices are commercially available, Rissman advises against anyone trying these units outside of supervised research. "The science is still in an early stage," he adds. "If you do this at home, you could stimulate your brain in a way that is unsafe, with too much current or for too long."

Rissman believes other areas of the brain also play important roles in retrieving memories. Their future research will aim to better understand the contributions of each brain region, as well as the effects of brain stimulation on other kinds of memory tasks.

Abstract

Functional neuroimaging studies have consistently implicated the left rostrolateral prefrontal cortex (RLPFC) as playing a crucial role in the cognitive operations supporting episodic memory and analogical reasoning. However, the degree to which the left RLPFC causally contributes to these processes remains underspecified. We aimed to assess whether targeted anodal stimulation—thought to boost cortical excitability—of the left RLPFC with transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) would lead to augmentation of episodic memory retrieval and analogical reasoning task performance in comparison to cathodal stimulation or sham stimulation. Seventy-two healthy adult participants were evenly divided into three experimental groups. All participants performed a memory encoding task on Day 1, and then on Day 2, they performed continuously alternating tasks of episodic memory retrieval, analogical reasoning, and visuospatial perception across two consecutive 30-min experimental sessions. All groups received sham stimulation for the first experimental session, but the groups differed in the stimulation delivered to the left RLPFC during the second session (either sham, 1.5 mA anodal tDCS, or 1.5 mA cathodal tDCS). The experimental group that received anodal tDCS to the left RLPFC during the second session demonstrated significantly improved episodic memory source retrieval performance, relative to both their first session performance and relative to performance changes observed in the other two experimental groups. Performance on the analogical reasoning and visuospatial perception tasks did not exhibit reliable changes as a result of tDCS. As such, our results demonstrate that anodal tDCS to the left RLPFC leads to a selective and robust improvement in episodic source memory retrieval.

Authors

Andrew J. Westphal, Tiffany E. Chow, Corey Ngoy, Xiaoye Zuo, Vivian Liao, Laryssa A. Storozuk, Megan A. K. Peters, Allan D. Wu and Jesse Rissman.

Return to top of page

| |

|

Jun 3 2019 Fetal Timeline Maternal Timeline News

Transcranial direct current stimulation, or tDCS, produces increased memory when applied to the Left Rostrolateral Prefrontal Cortex.

|