|

|

Developmental Biology - Brain Diseases

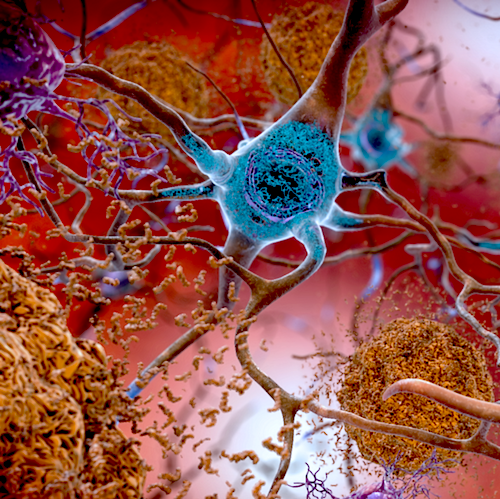

Alzheimer's May Have Tau Protein Subtypes

A possible biological reason Alzheimer's Disease (AD) progresses at different rates in different patients...

A study, led by Massachusetts General Hospital researchers, focuses on tau proteins, a well-known sign of AD. The work appears in the journal: Nature Medicine.

Tau can undergo a variety of modifications during the course of alzheimer's disease (AD). Physicians have long known that, from patient to patient, there can be substantial variation in its clinical presentation, including age of onset, rate of memory loss and various other clinical measures.

Higher levels of pathological tau in the brain are associated with more severe disease. However, there are few clues as to what causes this variation between patients.

The Mass General research team studied samples from 32 patients who were diagnosed with what is considered "typical AD" while living, confirming each diagnosis after death. However, the age at diagnosis and the rate of disease progression varied markedly among these patients.

More Detail

Researchers conducted an in-depth characterization of molecular tau proteins within each patient to create a more accurate picture of that person's disease.

This included using advanced mass spectrometry techniques to assess biochemical, biophysical and bioactivity assays for:

(1) levels of different species of tau

(2) tau's capacity to induce aggregations (called seedings)

(3) specific post-translational brain modifications.

What they found was "striking variation" in the presence of phosphorylated tau oligomers which are associated with greater tau spread, and importantly, worsening disease.

Specific modifications were associated with different degrees of severity and rate of disease progression.

Notably, specific molecular characteristics led to antibodies currently being considered for the therapeutic targeting of tau proteins in AD and associated diseases.

"We speculate there are different molecular 'drivers' of Alzheimer's progression, with each patient having their own set. This is similar to what we see in cancer, where there are several types of lung or breast cancer, for example, and the treatment depends on the particular molecular drivers in the patient's tumor."

Bradley Hyman MD PhD, Director, Alzheimer's Disease Research Center, Massachusetts General Institute for Neurodegenerative Disease (MIND).

Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) causes unrelenting, progressive cognitive impairments, but its course is heterogeneous, with a broad range of rates of cognitive decline1. The spread of tau aggregates (neurofibrillary tangles) across the cerebral cortex parallels symptom severity2,3. We hypothesized that the kinetics of tau spread may vary if the properties of the propagating tau proteins vary across individuals. We carried out biochemical, biophysical, MS and both cell- and animal-based-bioactivity assays to characterize tau in 32 patients with AD. We found striking patient-to-patient heterogeneity in the hyperphosphorylated species of soluble, oligomeric, seed-competent tau. Tau seeding activity correlates with the aggressiveness of the clinical disease, and some post-translational modification (PTM) sites appear to be associated with both enhanced seeding activity and worse clinical outcomes, whereas others are not. These data suggest that different individuals with ‘typical’ AD may have distinct biochemical features of tau. These data are consistent with the possibility that individuals with AD, much like people with cancer, may have multiple molecular drivers of an otherwise common phenotype, and emphasize the potential for personalized therapeutic approaches for slowing clinical progression of AD.

Authors

Simon Dujardin, Caitlin Commins, Aurelien Lathuiliere, Pieter Beerepoot, Analiese R. Fernandes, Tarun V. Kamath, Mark B. De Los Santos, Naomi Klickstein, Diana L. Corjuc, Bianca T. Corjuc, Patrick M. Dooley, Arthur Viode, Derek H. Oakley, Benjamin D. Moore, Kristina Mullin, Dinorah Jean-Gilles, Ryan Clark, Kevin Atchison, Renee Moore, Lori B. Chibnik, Rudolph E. Tanzi, Matthew P. Frosch, Alberto Serrano-Pozo, Fiona Elwood, Judith A. Steen, Matthew E. Kennedy and Bradley T. Hyman.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by a research agreement to Massachusetts General Hospital from Merck and by the NIH/NIA—5P50AG005134-35 (B.T.H.), 1RF1AG059789 (B.T.H.), 1RF1AG058674 (B.T.H.), 1P30AG062421 (B.T.H.), 1K08AG064039 (A.S.-P.).

The authors want to thank additional funding sources: Alzheimer’s Association (2018-AARF-591935 (S.D.), AACSF-19-617308 (A.L.)), the Martin L. and Sylvia Seevak Hoffman Fellowship for Alzheimer’s Research (S.D.), the Tau Consortium (B.T.H.), the Cure Alzheimer’s Fund (R.E.T.), the JPB Foundation (B.T.H. and R.E.T.), and the Swiss National Science Foundation (P2ELP3_184403 (A.L.)).

The authors also thank J. A. Gonzalez for helping with brain sampling, M. C. Potter for input in early phases of the work, P. Davies (Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York City) for generously providing with PHF1 antibody and M. Diamond (UT Southwertern, Dallas, Texas) for the generous gift of the TauRD-P301S-CFP/YFP cells.

This was a multi-institution, cross-disciplinary collaboration between clinicians, neuroscientists and neuropathologists. The team included Judith Steen PhD, Director, Neuroproteomics Laboratory in the F. M. Kirby Neuroscience Center, Boston Children's Hospital and Associate Professor, Harvard Medical School; and Matthew Kennedy PhD, Department of Neuroscience, Merck & Co.

About Massachusetts General Hospital

Massachusetts General Hospital, founded in 1811, is the original and largest teaching hospital of Harvard Medical School. The Mass General Research Institute conducts the largest hospital-based research program in the nation, with annual research operations of over $1 billion and comprises more than 9,500 researchers working across more than 30 institutes, centers and departments. In August 2019, Mass General was named #2 in the U.S. News & World Report list of "America's Best Hospitals."

Return to top of page.

|

|

Jun 25 2020 Fetal Timeline Maternal Timeline News

Individuals with AD, like people with cancer, may have multiple molecular incidents leading to their disorder. This knowledge will help individualize therapy for their particular AD. In this illustration, TAU appears BLUE as it affects a neuron. CREDIT National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

|

|