|

|

Developmental Biology - Gut & Lymph systems

Gut Cells Nurture Lymph Capillaries

Understanding how cilia grow and fat is digested in the small intestine...

Having just enjoyed a delicious summer BBQ, approximately eight hours latter, food molecules reach your small intestine. There, specialized lymph capillaries called lacteals will absorb fat nutrients.

Lacteal capillaries are different from other lymph capillaries. They continually regenerate at a slow, steady pace — even in adults. But how?

Now, a team of scientists led by KOH Gou Young at the Center for Vascular Research, Institute for Basic Science (IBS) in South Korea, has identified a subset of connective cells crucial to lymphatic growth. The findings are reported in Nature Communications.

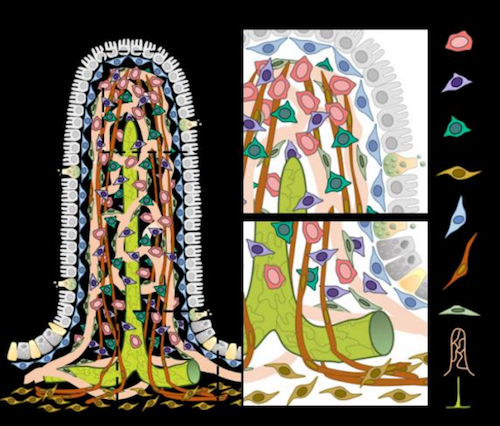

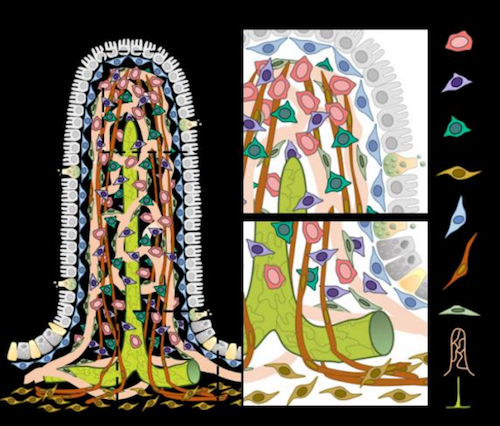

The small intestine is lined with fingerlike projections called villi, which themselves are lined with blood capillaries to absorb food molecules. Each vili is covered in epithelial, immune, vascular, connective and even neural cells. All co-exist to help the digestive processing of all that BBQ.

The gut environment must also cope with water being secreted and reabsorbted, as well as the muscular activity moving food through the intestines. How all these complex mechanisms work in harmony is still to be unraveled. However, researchers have identified a new piece in the puzzle.

Two proteins, YAP and TAZ, found in intestinal stromal cells appear to affect lacteal growth. Mice with hyperactivated YAP/TAZ, grew atypical lacteals unable to absorb dietary fats.

"Lacteals in these mice looked like tridents, yet all we did was manipulate cells surrounding the lacteals, not the lacteals themselves."

Seon Pyo Hong,

Center for Vascular Research, Institute for Basic Science (IBS), Daejeon, Republic of Korea, and co-author of the study.

Researchers were able to identify that intestinal stromal cells have several subtypes after using gene expression with each villi. Three new cell populations were identified to be secreting VEGF-C an essential molecule for lymphatic growth - as well as YAP and TAZ being activated.

"We were very surprised to see such heterogeneity in a cell population considered homogeneous."

MyungJin Yang, Center for Vascular Research, Institute for Basic Science (IBS), Daejeon, Republic of Korea

and co-author of the study.

Over all, researchers found that mechanical stimulation activates osmotic stress which regulates YAP/TAZ activity in stromal cells. Which in turn released VEGF-C and can account for lacteal growth.

"This result implies a crucial link between the physiology of the intestinal environment and biological interactions between cell types," explained Hyunsoo Cho co-author of the study.

"We are interested in investigating how each newly identified cell type works in healthy and diseased conditions."

Gou Young Koh, Center for Vascular Research, Institute for Basic Science (IBS); Graduate School of Medical Science and Engineering, Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST), Daejeon; Biomedical Science and Engineering Interdisciplinary Program, KAIST, Republic of Korea.

Abstract

Fibroblastic reticular cells (FRCs) are immunologically specialized myofibroblasts of lymphoid organ, and FRC maturation is essential for structural and functional properties of lymph nodes (LNs). Here we show that YAP and TAZ (YAP/TAZ), the final effectors of Hippo signaling, regulate FRC commitment and maturation. Selective depletion of YAP/TAZ in FRCs impairs FRC growth and differentiation and compromises the structural organization of LNs, whereas hyperactivation of YAP/TAZ enhances myofibroblastic characteristics of FRCs and aggravates LN fibrosis. Mechanistically, the interaction between YAP/TAZ and p52 promotes chemokine expression that is required for commitment of FRC lineage prior to lymphotoxin-? receptor (LT?R) engagement, whereas LT?R activation suppresses YAP/TAZ activity for FRC maturation. Our findings thus present YAP/TAZ as critical regulators of commitment and maturation of FRCs, and hold promise for better understanding of FRC-mediated pathophysiologic processes.

Authors

Sung Yong Choi, Hosung Bae, Sun-Hye Jeong, Intae Park, Hyunsoo Cho, Seon Pyo Hong, Da-Hye Lee, Choong-kun Lee, Jin-Sung Park, Sang Heon Suh, Jeongwoon Choi, Myung Jin Yang, Jeon Yeob Jang, Lucas Onder, Jeong Hwan Moon, Han-Sin Jeong, Ralf H. Adams, Jin-Man Kim, Burkhard Ludewig, Joo-Hye Song, Dae-Sik Lim and Gou Young Koh.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Hyun Tae Kim for technical assistance. S.Y.C. (2018R1D1A1B07044974) and H.B. (NRF- 2014-Fostering Core Leaders of the Future Basic Science Program/Global Ph.D. Fellowship Program Grant) are supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government. This study was supported by the Institute for Basic Science (IBS-R025-D1, G.Y.K.) funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT and Future Planning, Korea and the Human Frontiers Science Program (RGP0034/2016, B.L. and G.Y.K.).

The authors declare no competing interests.

Return to top of page.

|

|

Aug 20 2020 Fetal Timeline Maternal Timeline News

This image shows fingerlike projections that cover the intestinal wall and absorb nutrients in the small intestine. During digestion, hydrophilic nutrients, such as glucose and amino acids, are absorbed by blood capillaries. On the other hand, hydrophobic nutrients, such as lipids, are taken in by specialized lymphatic capillaries called lacteals. The graphics also shows five types of connective cells (vFB1, vFB2, vFB3, FB4, and FB5), three of which were identified in this study, as well as smooth muscle cells (SMC), mural cells (MC), blood and lymph capillaries (lacteals).

CREDIT The Authors.

|

|