|

|||||||||||||||

|

CLICK ON weeks 0 - 40 and follow along every 2 weeks of fetal development

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

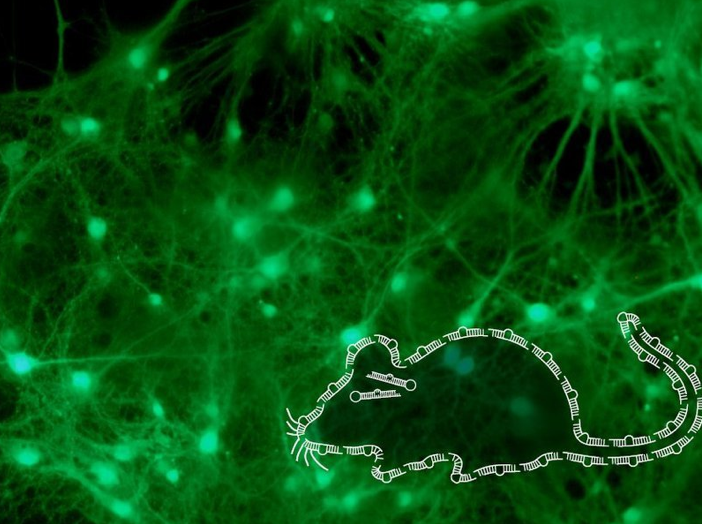

A molecule for making friends Meeting new people can be both stressful and rewarding — and may involve the same molecule. New research conducted in Alon Chen's Department, and led by Yair Shemesh and Oren Forkosh of the Max Planck Institute of Psychiatry, suggests Urocortin-3, a molecule which regulates stress — may also determine how willingly we leave our preferred social group to strike up new relationships. Working with mice, researchers identified a stress mechanism that appears to act as a "social switch." It causes mice to either increase interactions with "friends" and "acquaintances" or reduce those interactions and seek to meet strangers instead. As a similar stress system operates in humans, their findings suggest a similar mechanism regulates social challenges in humans. Disruptions in this mechanism might be responsible for difficulties in people affected by social anxiety, as well as in those with autism, schizophrenia or other disorders.

Scientists used two behavioral setups to study how mice cope with the challenge of interacting with other mice. One, a "social maze," in which a mouse can choose to interact through a mesh with either familiar mice or strangers, or avoid interaction all together. The other was a special arena, in which mice were tracked with video cameras while observations were analyzed using a computer algorithm created for that purpose. This unique setup enabled researchers to quantify various types of interactions — approach, contact, attack or chase — among individual mice within the undisturbed group over several days. The results revealed that a molecular mechanism involved in stress management in mice brains determines their behavior toward other mice. A small signaling molecule, Urocortin-3, attaches to a receptor on the surface of neurons, binding them to the molecule.

Mice with high levels of Urocortin-3 in their brain actively seek out contacts with new mice behind the mesh, even ignoring their own group. But when the brain activity of Urocortin-3 and its receptor are blocked, the mice chose to socialize mainly within their group, avoiding contact with strangers. Adds Oren Forkosh: "In nature, mice live in groups and the social challenges they face differ from their relationship with intruders. It therefore makes sense for a brain mechanism to produce different types of social coping in these two situations. In humans, this mechanism might be involved whenever we consider moving out of our parents' home, getting a divorce or changing jobs or apartments." Abstract Original publication: |

Jul 27, 2016 Fetal Timeline Maternal Timeline News News Archive  A specific molecule — Urocortin-3 — regulates stress-induced behavior in mice. Image Credit:© Tali Wiesel /Weizmann Institute of Science.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||