|

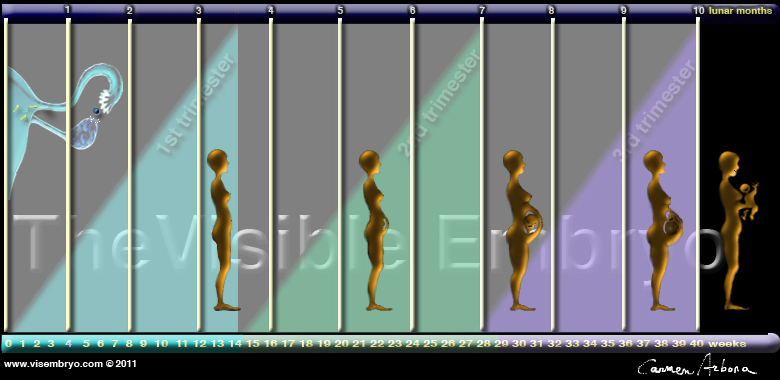

CLICK ON weeks 0 - 40 and follow along every 2 weeks of fetal development

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Home | Pregnancy Timeline | News Alerts |News Archive Mar 27, 2015

|

Solving the "obstetrical dilemma" For decades, an explanation for why childbirth is so difficult, painful and dangerous had made the assumption that women's hips were not wide enough. The argument known as the "obstetrical dilemma," suggested that millions of years ago, our bipedal ancestors had made a trade-off in order to evolve into out current two legged state. Wider hips for childbirth were sacrificed for narrow hips and improved walking and running.

Rsearchers at Harvard in conjunction with colleagues at Boston University and Hunter College, found no connection between hip width and efficient locomotion, suggesting scientists have seen the problem of difficult birthing in the wrong way. The study is described in a March 11 paper published in PLOS ONE.

The study grew out of research Warrener conducted at Washington Univertsity in St Louis, Missouri. Warrerner was supervised by Herman Pontzer, professor of Anthropology at Hunter College, himself a former Ph.D. student under Lieberman, and Eric Trinkaus. At the same time, Lieberman and Kristi Lewton, a former postdoctoral fellow in Lieberman's lab (now at Boston University) were exploring the same problem. When the two teams discovered they'd been working on similar tracks, they combined their efforts into a single study. "This idea - that wider hips make you less efficient - has been taught for 30 years," said Herman Pontzer, professor of Anthropology at Hunter College. "Good science is about taking a critical look at things we take for granted. This is going to change the way we teach Anthropology 101 everywhere, and it's going to change the way we teach about human evolution and walking adaptations and the birth of babies. I think it's a great example of how new things can be uncovered when you really bother to look deeply at accepted ideas." At the heart of why those earlier ideas were fundamental problems with the simple biomechanical models used to understand the forces acting on the hips. "If we only had a pelvis and a femur, the old model might be correct," Lieberman said. "But we also have a shank, and an ankle, and a foot. And when you place your foot on the ground, forces don't just shoot straight up from the ground to your hip. By the time they arrive at your hip, they aren't acting on your body in this idealized way." To understand what was really happening, researchers turned to a biomechanical technique known as inverse dynamics. "Essentially, we measured the chain reaction of forces as they move through the body, starting at the foot and progressing up the leg to the hip," Warrener said. And as Warrener and Lieberman discovered, the old models simply didn't make sense.

In the case of the pelvis,there are two important moment arms. One extends from the center of the hip joint to the body's center of gravity. The other extends from the center of the hip joint to the abductor muscles along the side of the hip. They stabilize the hip when only one foot is on the ground. According to basic rules of physics — the longer the moment arm is from the hip to the center of the pelvis, the more force the hip abductor muscles produce to stabilize the body, requiring more energy. As a result, it was assumed people with wider hips - including most women - need more energy to walk and run. When Warrener and colleages began studying a variety of body shapes, however, they didn't find enough supporting evidence.

If wider hips don't equate with less efficient walking or running, it begs two questions - why has the incorrect assumption persisted for so long, and why don't all women have the widest hips possible to allow for easier childbirth? On the first assumption, cultural biases may be the answer. Until recently, Lieberman said, portrayals of hunter-gatherer societies imagined that men were responsible for hunting and far more active than women. More recent data, however, show this is untrue. Liberman: "For most of evolutionary history, women have done a great deal of work. Hunter-gatherer women walk, on average, nine kilometers (about 5.6 miles) a day, so they would have to be just as efficient as men. In addition, women are metabolically responsible not just for themselves but also for their infants. "They have to pay the metabolic costs of gestation and nursing, and they have to feed dependent offspring, so they almost always need to save energy. Women are under very strong selection to be efficient. So you'd predict they would also be efficient at walking as well — and that's exactly what we found." While the researchers don't have an answer for why women don't have the widest possible hips needed for easier birth, one hypothesis advanced by Warrener and colleagues suggests that the problem may be that the modern world is drastically different from any environment in human history. Lieberman: "One idea my lab studies is the idea of mismatch. Our bodies are not always very well adapted for the novel environments in which we now live." Going forward, Warrener believes researchers need additional data before they can fully understand how the modern environment has changed birth outcomes.

Abstract

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||