|

|

Fetal Timeline Maternal Timeline News News Archive Sep 1, 2015

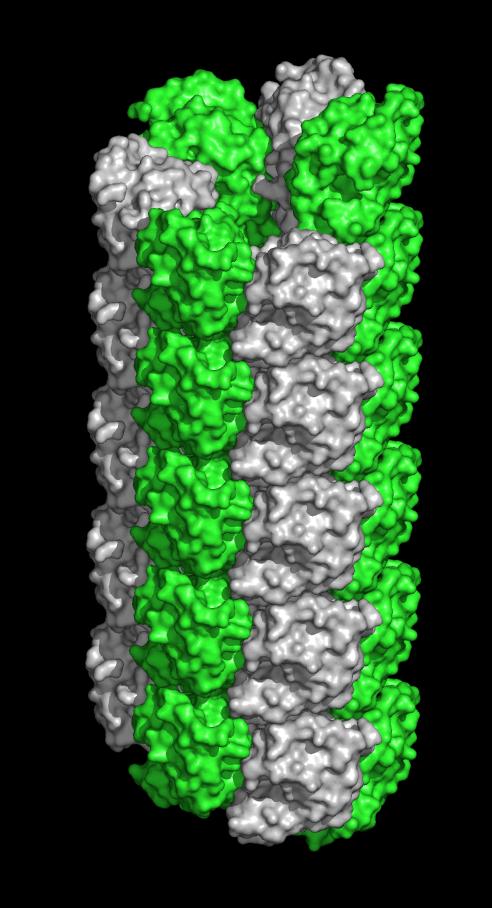

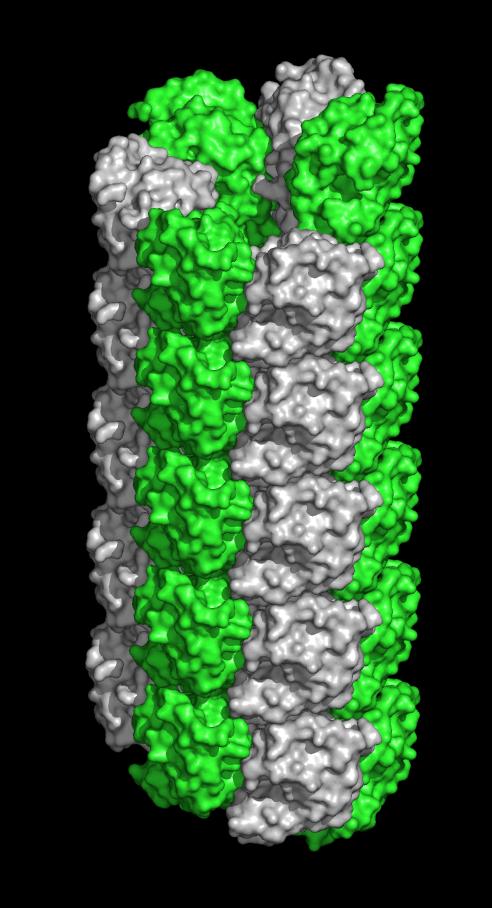

SLLP1 filament along the sides of the sperm head. Each monomer alternately colored.

Image Credit: Heping Zheng, Ph.D., University of Virginia School of Medicine

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Do sperm wield tiny harpoons?

Could sperm harpoon the egg to initiate fertilization? That's a possibility raised after finding spiky filaments on the sperm head. The spikes may play a role in sperm and egg fusion.

University of Virginia School of Medicine has discovered that a protein in the head of the sperm forms spiky filaments, suggesting that these tiny filaments may lash the sperm to its target — the egg.

The finding, 14 years in the making, made the cover of the journal Andrology. It represents a significant step in fine dissection of a sperm's acrosomal matrix, an organelle located in the sperm head, while suggesting a new hypothesis about what happens during fertilization.

"This finding has really captured our imagination. One of the major proteins that is abundant in the acrosome [the sperm head] is crystallizing into filaments. We now postulate they are involved in penetrating the egg — that's the new hypothesis emerging from this finding. This leads to a whole new set of questions and new hypotheses about the very fine structure of molecular events during fertilization."

John Herr PhD, Professor of Cell Biology and Biomedical Engineering, University of Virginia School of Medicine

The discovery is the result of a longstanding collaboration between Herr's lab and the lab of Wladek Minor PhD, of the Department of Molecular Physiology and Biological Physics. Years ago, Herr's lab discovered the protein now seen to form filaments. They dubbed it sperm lysozyme-like protein 1 (SLLP1). This protein is a member of a family of proteins now known to reside exclusively inside the acrosome.

Herr's lab, however, had no way to determine the shape and structure of the protein. Minor's lab figured that out, first by capturing the protein within a stable crystal, then cooling the crystal to cryogenic temperatures to prevent decay, then blasting the crystal with X-rays. By examining how those X-rays were bent, they could calculate the shape of the protein, somewhat like mapping a shipwreck using sonar.

It was not easy, requiring many attempts and analysis. But in the end, they were able to produce one of the first descriptions of a sperm protein.

"This is an important protein. It is the first crystal structure from a protein within the sperm acrosome. It is also the first structure of a mammalian sperm protein with a specific oocyte-side binding partner characterized. To our knowledge, only nine proteins specifically obtained from mammalian sperm have known structures."

Heping Zheng PhD, lead author of the paper

The new understanding of the structure will now act as a map for Herr and other reproductive biologists exploring how fertilization occurs.

Herr explains: "At the very fundamental level, understanding that fine molecular architecture leads me, the biologist, to be able to posit new functions for this family of proteins my lab has discovered in the acrosome."

Abstract

Sperm lysozyme-like protein 1 (SLLP1) is one of the lysozyme-like proteins predominantly expressed in mammalian testes that lacks bacteriolytic activity, localizes in the sperm acrosome, and exhibits high affinity for an oolemmal receptor, SAS1B. The crystal structure of mouse SLLP1 (mSLLP1) was determined at 2.15 Å resolution. mSLLP1 monomer adopts a structural fold similar to that of chicken/mouse lysozymes retaining all four canonical disulfide bonds. mSLLP1 is distinct from c-lysozyme by substituting two essential catalytic residues (E35T/D52N), exhibiting different surface charge distribution, and by forming helical filaments approximately 75 Å in diameter with a 25 Å central pore comprised of six monomers per helix turn repeating every 33 Å. Cross-species alignment of all reported SLLP1 sequences revealed a set of invariant surface regions comprising a characteristic fingerprint uniquely identifying SLLP1 from other c-lysozyme family members. The fingerprint surface regions reside around the lips of the putative glycan-binding groove including three polar residues (Y33/E46/H113). A flexible salt bridge (E46-R61) was observed covering the glycan-binding groove. The conservation of these regions may be linked to their involvement in oolemmal protein binding. Interaction between SLLP1 monomer and its oolemmal receptor SAS1B was modeled using protein–protein docking algorithms, utilizing the SLLP1 fingerprint regions along with the SAS1B conserved surface regions. This computational model revealed complementarity between the conserved SLLP1/SAS1B interacting surfaces supporting the experimentally observed SLLP1/SAS1B interaction involved in fertilization.

Findings Published

The structure has been detailed in an article published in Andrology by Heping Zheng, Arabinda Mandal, Igor A. Shumilin, Mahendra D. Chordia, Subbarayalu Panneerdoss, John Herr and Wladek Minor.

The Herr/Minor collaboration had already produced two journal covers.

Return to top of page

|